Boutique buds

What underground mom-and-pop growers did while we debated legalization

What underground mom-and-pop growers did while we debated legalization

By Adrian Higgins. Sunday, October 31, 2010; W08

OAKLAND, Calif. —Jeremy Ramsay leads me through the back corridor of the nondescript one-story building that is Harborside Health Center. His bright little office is windowless but cheery, its white walls reflecting the glow of fluorescent lights, banks of them. Layer on layer of shop lights are feeding dozens — hundreds — of six-inch rooted cuttings of marijuana.

Ramsay is manager, clones, a title straight out of “Brave New World.” His babies are weeks away from bulking up and setting the bizarre clusters of mind-altering flower buds, but even in youth the lobed leaves, slender and saw-toothed, are distinctive, iconic, ominous.

If your last joint was experienced while coughing along to a Bob Dylan album in the ’70s, Ramsay’s offerings will seem incredibly far out. I mean, incredibly.

On the other side of the building, patrons are spoiled by a choice of varieties whose pothead names are lagging behind the contemporary, therapeutic image of marijuana — sorry, cannabis — in all its boutique wonder. Kushage bestows a high helpful for brainstorming. Sour Cream is so calming. Kish is fruity but potent. Martian Mean Green flowers up a stench, but the buds burn real stoney.

I have come to California to see a quasi-underground horticultural marvel: growers, breeders and dispensers who have quietly brought the hemp plant to a level not seen in its rocky 6,500-year history with humankind.

When alcohol was chased underground during Prohibition, the resulting clandestine booze was notoriously rank — the paint-stripping moonshine, the barely drinkable homemade wine. Marijuana, however, has undergone radical advances since the war on drugs sent it deep into the shadows 25 years ago.

In the now semi-open marijuana landscape of Northern California, I find a plant species transformed. Skilled mom-and-pop breeders have developed hundreds of high-performing cultivated varieties, and home hobbyists have grown them to perfection using new techniques and technologies. Marijuana has never been more potent, more productive and more varied in its appearance, flavor and effect. It is twice as productive as in the 1980s and three or more times as potent. As the supply has increased, the value has dropped or stagnated, from $5,000 a pound 15 years ago to about $3,000 today. By the ounce, Ramsay says, the choicest varieties still sell for as much as $400, but the cannabis connoisseur can pick up high-grade strains for half that amount today.

Many Americans of a certain age will remember that in the 1970s, seedy homegrown pot was reviled for its raw, throat-burning quality. Now dope-smoking locavores steer clear of cheap, low- and mid-grade weed in favor of organically grown boutique strains. They speak of “presentation” and varieties so agreeably complex that “you inhale one flavor and exhale another.” Just as in the vineyards of the Napa Valley a few miles to the north, complexities come from the soil, from the fruits of labor, from careful breeding. Suddenly, pot has terroir.

It’s surreal, even for California, but it may be our future.

Fourteen years after Californians approved medical marijuana, they return on Tuesday to consider Proposition 19. This would allow people 21 or older to become the first in the nation to legally cultivate, possess and use small amounts of marijuana, and let local governments license commercial growers and retailers.

If it doesn’t pass, its backers vow to return. If it does pass, California will become even more cannabis-friendly than the Netherlands.

Washington, D.C., and 13 states besides California are at early points along this path, allowing the chronically sick access to marijuana (in defiance of federal law). Advocacy groups consider the newly adopted D.C. law, still awaiting implementation, to be so restrictive as to be virtually impractical. It doesn’t allow home cultivation, permits just five to eight growing centers and dispensaries, and limits each to just 95 plants. Meanwhile, federal sentencing mandates require a five-year prison term for possession of 100 or more. Maryland judges can lower the fines in medical marijuana cases, but you still may be arrested and convicted; Virginia has no medical marijuana law.

I am thinking about the District’s limits on plants as I sit in Jeremy Ramsay’s little cuttings room, where there are enough plants to fill 30 D.C. dispensaries. I had just come from another establishment, where I had seen hundreds of full-size stock plants in growing rooms, bathed in the sallow light of high-pressure sodium lamps. Even without Prop. 19, hundreds of thousands of Californians have received doctor’s recommendations to use the drug since medical marijuana was legalized; estimates range from 400,000 to 700,000 residents. In theory, given the state’s six-plant limit, they could have collectively grown millions of plants lawfully.

In Oakland’s openly drug-tolerant district, I am taken to a cafe-style dispensary where buyers pore over the choicest buds for smoking and buy cuttings for $12 apiece, to a medical marijuana club where three members are drawing on skinny cannabis cigarettes, and to a curtained speak-easy where the patrons are enjoying a game of pool. The air is heavy with that pungent aroma of dope, and I am wondering: Was this what Prohibition felt like on the eve of repeal?

“I think what happens with medical marijuana is that it becomes impossible to make it medical marijuana alone,” said Richard Lee, head of a medical marijuana trade school in Oakland named Oaksterdam University and the originator of Prop. 19. “It’s a relatively safe substance. It’s safer than alcohol and healthier than prison.”

Those caught up in the violent web of the illegal marijuana world may have a different view, though an abiding argument of cannabis advocates is that full legalization will chase the violent criminals away. This is rejected by federal drug officials, who say that black market providers will remain in the game and that legalization will increase the availability and abuse of marijuana as prices continue to drop.

Marijuana use peaked in the late 1970s, when 60 percent of high school seniors had admitted to smoking pot. Then the baby boomers grew up, Nancy Reagan just said no, and for those outside this counterculture, the drug world seemed an unappetizing food chain, with violent drug cartels at one end and dopey kids at the other. Marijuana, of course, did not go away but flourished underground.

Ironically, the government’s international war on drugs proved an enormous boon to marijuana cultivation in the United States. By 2002, as much as 10,000 metric tons of cannabis were cultivated annually, according to a government estimate. Jon Gettman, a criminal justice scholar, used this figure to argue that marijuana had become the nation’s biggest cash crop, with a conservative value of $35 billion at a time when the corn harvest was $23 billion and soybeans $17.6 billion.

The original estimate may be too great, officials now say, though Drug Enforcement Administration raid reports show a signficant increase in the number of plants seized in California — from 1.2 million in 2003 to 7.5 million last year.

In the past decade, according to the Justice Department, Mexican drug organizations have expanded their outdoor growing operations in the United States from the West Coast to such states as Arkansas, Georgia and even frigid Wisconsin. This, even as 28,000 people have died in bloody Mexican drug wars in just the past four years. Meanwhile, tightknit groups of ethnic Vietnamese and Chinese growers have increased the number of large-scale indoor operations from California to New England, according to the department’s National Drug Intelligence Center.

These are the scary images of commercial syndicates. But what of the lone hobbyist raising plants in a tiny growing tent in an apartment, or more openly in garden beds as state laws are relaxed?

Such a base of marijuana gardeners also has been growing exponentially over the past three decades. Gettman, who teaches at Shenandoah University and lives in Lovettsville, Va., calls it the “atomization” of marijuana cultivation that fuels a singularly American fixation for growing crops to maximize yield. Gettman, who is also coordinator of the Coalition for Rescheduling Cannabis, seeking to relax federal marijuana laws, says the government’s assertion that most indoor cannabis cultivation is undertaken by Asian organizations is “ridiculous.”

“A lot of Americans really, really like to grow pot,” he said.

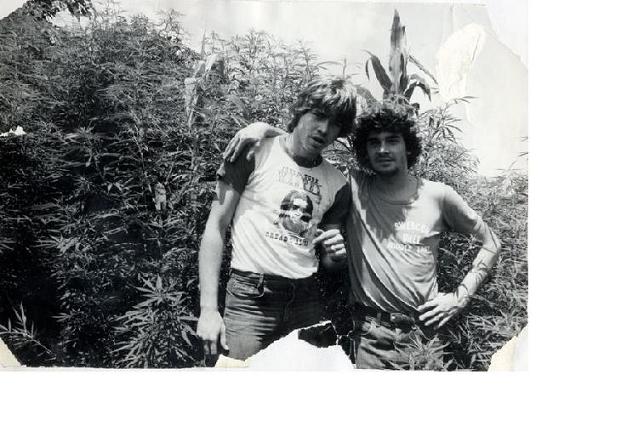

To meet such a cultivator, I drive north of Oakland into Sonoma County to see an Anglo named George van Patten, who is better known to his avid readers as his Latino alter ego, Jorge Cervantes.

In the 1980s, he ran a hydroponics store in Portland, Ore., and published one of the first books on how to grow marijuana: self-written, -illustrated, -printed and -bound because no publisher would dare touch it. The book became the foundation for more editions, fresh volumes and translations into Spanish, German, French and Italian. His latest book is about the basics of marijuana cultivation and is aimed at novices.

Approaching Sonoma, I see roadside fields of vines heavy with purple-black grapes, and through the town squat palms line the streets like upended joints, cartoonish and mocking. The sky is blue and cloudless, the sun impossibly bright. There is none of the fungal-inducing humidity of Washington or the wretched night heat that weighs so heavily on our garden plants. You could grow anything here, I’m thinking, if you had the water.

Cervantes had sent me publicity pictures of himself in a hammock, holding his pet dachshund and surrounded by a forest of container-grown cannabis. His black hair fell to his shoulders.

When I pull into his street, I wonder whether I have take a wrong turn: The gabled homes are tidy and uniform, and the neighborhood exudes an air of suburban rectitude. Cervantes is outside to greet me, but he is older and smaller than he appeared in the photos, his flowing hair now grayish blond. We enter his home, past a neat front lawn framed by white roses and purple agapanthus. The back garden has all the signs of a formerly basic landscape under fresh assault by an incurable gardener.

A new redwood privacy fence wraps around a large but unplanted garden bed. Since December, Cervantes has excavated five cubic yards of rock and sticky clay soil, and added 100 yards of enriched, amended soil. The side garden is dominated by three raised beds, two of which house ripening tomatoes, peppers and other summer vegetables. The third bed holds six marijuana plants, heavily branched, lush and green. Clearly, they have received loving care — good soil, ample moisture and, as it turns out, pricey bat guano at $70 a box. They are growing under shade cloth in a raised bed enriched with bark chips, sand, chicken manure, compost and sterilized bone meal. Now, in late August, they are three feet across and at least as high.

Cannabis is a botanical loner, its sole relative the hopvine used to flavor beer. It also is an annual, but unlike other annuals, its plants are single sex. A male blooms with pollen, a female plant has clusters of ovaries, which produce seeds, but only if fertilized with pollen.

The inferior dope produced by criminal organizations typically contains stems, leaves and seedy buds and the rankest herb is combined with filler and pressed into bricks. But a hobby grower such as Cervantes knows that the highest quality and most potent marijuana is made primarily from the unpollinated female flower buds, of choice strains. Where once the wild article was scrawny and grudging — ditch weed — these modern cultivated varieties are bushy and packed with plump, resinous buds. This choice, seed-free herb is known as sinsemilla (Spanish for “without seed”).

Marijuana, like chrysanthemums and poinsettias, is spurred to flower by the shorter days of late summer. But its bloom has none of the innate beauty of, say, a daisy or a rose. Pollinated by the wind, the blossoms have no need to pretty themselves for bees or butterflies. Each flower is wrapped tightly in a drab sheath, from which it sends up a pair of hair-like tubes, pistils in search of the pollen that the artful gardener denies them.

Cervantes removes the shade cloth so I can get a good look at these baby flowers. Weeks away from harvest, they are the size of a pea and just beginning to show their short blond hairs. Half of the varieties are of Bubba Kush, the other Purple Kush, a favored medical strain for treating both pain and depression.

Over the next few weeks, the plants’ maiden blossoms will proliferate and form clusters, most noticeably at the branch tips. Lacking pollination, the plants will produce increasing numbers of individual flowers in a vain effort to attract a mate. The cluster at the top of the main stem will become so congested that it may stretch 18 inches or more and contain hundreds of engorged flowers. Among growers, the ugliness of the individual flower is more than surpassed by the spectacle of the huge bud spike.

Apart from the gathering odor, which can be strong and pungent, the maturing inflorescence is marked by a number of striking elements. It contains small, underdeveloped leaves that are trimmed at harvest. The pistils often change from their blond color to become threads of amber. The buds and leaves appear to be frosted with sugar crystals, and in some varieties, such as Purple Kush, the buds have a purple-blue cast.

After harvest the buds are cured and dried to permit storage, to preserve and intensify the psychoactive compounds and to prevent crop-destroying mold. Cervantes hopes to harvest 4 to 6 ounces from each plant, enough for about 300 cigarettes. He adds a little tobacco to his joints, a habit he picked up after six years in Spain as a self-imposed exile of the George W. Bush years.

In his office, he takes out some stored buds, and I look at them under a microscope: The surfaces are covered in minute crystalline structures, like the stalked eyeballs of snails, but glasslike. These fragile trichomes, which give modern varieties their frostiness, are full of a compound called THC, one of about 100 cannabinoids but the principal one for producing the high. The trichomes grow most abundant and THC-rich just as the plant matures. The gardener must be watchful.

As I am pondering this, the air is suddenly full of the acrid aroma of an ignited joint. Cervantes has a doctor’s recommendation to take marijuana for insomnia and backache. He says he smokes from one to four joints a day. Everyone I meet on this journey seems to have some sort of chronic medical complaint, ranging from anxiety to insomnia, from attention deficit disorder to a condition called cyclic vomiting syndrome.

For those in their 30s, like Ramsay, the state legitimization of growing and using marijuana, for medical purposes at least, is a world they have grown up with. But for an earlier generation that came of age in the hippie era, then saw it all move underground, the present period of conditional legalization comes after years of living outside the law and within a dark realm of fear, stigma and seedy transactions. “I cried the first time I bought it” legally, said Cervantes, who is 56. “It’s a whole different feeling. You can grow it and not be afraid.”

His hydroponics store was closed in a nationwide DEA raid in the late 198os. Fearing prosecution, he went underground and spent increasingly long periods in the safe haven of the Netherlands. In Holland, he met other pot refugees from the United States and other countries, and this place of exile became a center of a nascent interest in breeding new varieties.

Hobby growers and breeders today collectively make this plant the subject of “the biggest seed-breeding program in the world,” says Ed Rosenthal, a horticultural instructor at Oaksterdam University.

There are two basic breeding lines in cannabis hybridization: the wild species, Cannabis sativa, and a subspecies named indica. The sativa is a lanky, slow-growing but potent weed hailing from tropical and subtropical climes. Indica is native to Afghanistan and east along the foothills of the Himalayas, and is distinguished by its short, bushy habit and broader leaves. Other strains naturally developed with distinctive regional traits from Mexico to equatorial Africa to Thailand.

It’s a simple proposition to create what might be an alluring hybrid between a male and female plant. What is more difficult and painstaking is to develop a seed strain that will replicate itself consistently. This requires raising several generations of plants, and can take from 18 months to five years or more.

In Holland in the 1980s, landmark strains such as Skunk No. 1 and Haze launched a breeding frenzy that spawned other classic varieties, including White Widow, Northern Lights and Big Bud. The hybridizers were tapping the myriad genes of sativas, indicas and naturally occurring varieties to increase the yield, shorten the flowering cycle and make the plants bushier for indoor cultivation.

Oaksterdam University’s Rosenthal, writing in “The Big Book of Buds, Volume 3,” says the cannabis world is now seeing a fourth breeding wave whose intent is to produce plants that are “tweaked to produce connoisseur highs.”

At Harborside, Ramsay hands me a list of all of the clones he has received in recent months. The list runs to 222, and includes such choice varieties as Casey Jones, described in “The Big Book of Buds” as a sativa-rich hybrid that is “up, trippy”; Blue Cheese, indica-dominant and “highly euphoric” but “very functional”; and the sativa-heavy Purps, “giggly, blissful.”

THC is the engine of the high, but the other aromatic essential oils drive the nature of the intoxication and the palliative effects.

But how has herb with 14 percent THC changed the high? It’s quicker to take effect and a loaded THC variety like Train Wreck will be “more stoney,” Cervantes said.

Experts such as Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, say the high potency has transformed marijuana for many users into a drug that can induce psychosis and paranoia and increase addiction. “The marijuana people were smoking 20 years ago was much less potent, and that explains why in the past medical consequences associated with marijuana were relatively rare,” she said. “Now we are seeing an increase in [emergency room] admissions.”

Breeders are now making varieties that are lower in THC but higher in another cannabinoid called CBD, considered helpful in treating illness without the high.

Across town, I meet Jeff Jones, a longtime cannabis activist and instructor at Oaksterdam University who runs a marijuana equipment store a couple of blocks from the school. The growing tents he sells speak volumes about the advanced state of home production. Designed for use indoors with their own lighting systems, they permit furtive cannabis cultivation as easily in, say, Silver Spring as in Northern California.

“I saw them ramping up about five or six years ago,” Cervantes says. “They are really a big thing now.”

Measuring just 4-by-4-feet and rising to about seven feet, Jones’s floor model is made of a rigid fabric that is black outside and a reflective silver within. When zippered shut, none of the light escapes, and the grower can install a filtration system that not only moves air inside but prevents marijuana odors from escaping. The plants begin to reek at the flowering stage, and some varieties are so stinky you can smell them through brick walls.

The grower can raise plants either in soil or hydroponically, in an inert medium such as coconut fiber. In the hydroponic method, a reservoir holds water and nutrients, which are either pumped or wicked to the root zone.

The home grower can get started for less than $1,000.

Growing indoors has obvious advantages over outdoor cultivation: It is private, crops can be grown year-round, and, because you manipulate the hours of light, you can raise four to six crops a year, compared with one or two outdoors.

On the downside, indoor cultivation uses a lot of electricity, which is not only bad for your wallet and the environment but is a way for investigators to detect illicit operations. The latest advances are in LED lights, which use far less electricity and don’t need cooling, but can cost as much as $2,000 a unit.

Gettman said people are “flocking” to hydroponic suppliers. A habitual smoker could easily go through $5,000 worth of marijuana a year.

Some growers are wary of Prop. 19, believing its passage would attract large-scale commercial nurseries. Already, there is speculation that wineries in Napa and Sonoma would get into it, as would big tobacco.

Separately from Prop. 19, the city of Oakland is preparing to issue four permits to allow large-scale commercial cultivation of marijuana for medical users. Harborside’s founder and chief executive, Steve DeAngelo, remarkable for his pigtails and porkpie hats, is considering throwing one of them (hat, that is) into the ring. He joins me in Ramsay’s cutting room cum office. “The debate moves from whether cannabis is going to be legal to how cannabis is going to be legal,” he said.

Rosenthal sees a day when cannabis will be grown like another popular and ubiquitous crop. “I like the tomato model,” he said, rattling off a possible hierarchy of breeders and growers: giant industrial companies; regional companies; farmers; individuals raising marijuana for cash from their own big back yards, then home growers. “There’s room for everybody in that model,” he said. “But with all the commercial ways tomatoes are grown, home growers still grow the most tomatoes in the U.S.”

So Jorge Cervantes’s little backyard patch offers a glimpse of an America he and his fellow cannabis comrades see as becoming not just normal but the foundation of an openly vast marijuana-growing nation. Botanically, Cannabis sativa has undergone a quiet revolution since the baby boomers came of age.

DeAngelo argues that just as the plant has changed, so must we, in our relationship to it. Marijuana, he says, can teach us how to be kinder to the earth and our fellow travelers on it. “We are at a different time in the history of this plant,” he said.

Adrian Higgins is a Washington Post staff writer. He can be reached at higginsa@washpost.com.