POLITICS OF PAIN

State pushes prescription painkiller methadone, saving millions but costing lives

State pushes prescription painkiller methadone, saving millions but costing lives

To cut costs, Washington steers Medicaid patients to a narcotic that costs less than a dollar a dose. The state insists methadone is safe.

But hundreds die from it each year — and more than anyone else, it’s the poor who pay the price.

Assign a dot to each person who has died in Washington by accidentally overdosing on methadone, a commonly prescribed drug used to treat chronic pain. Since 2003, there are 2,173 of these dots. That alone is striking, a graphic illustration of an ongoing epidemic.

But it’s the clusters that pop out — the concentration of dots in places with lower incomes.

Everett, whose residents earn less than the state average, has 99 dots. Bellevue, with more people and more money, has eight. Working-class Port Angeles has 40 dots. Mercer Island, upscale and more populous, has none.

For the past eight years Washington has steered people with state-subsidized health care — Medicaid patients, injured workers and state employees — to methadone, a narcotic with two notable characteristics. The drug is cheap. The drug is unpredictable.

The state highlights the former and downplays the latter, cutting its costs while refusing to own up to the consequences, according to a Seattle Times investigation that includes computerized analysis of death certificates, hospitalization records and poverty data.

Methadone belongs to a class of narcotic painkillers, called opioids, that includes OxyContin, fentanyl and morphine. Within that group, methadone accounts for less than 10 percent of the drugs prescribed — but more than half of the deaths, The Times found.

Methadone works wonders for some patients, relieving chronic pain from throbbing backs to inflamed joints. But the drug’s unique properties make it unforgiving and sometimes lethal.

Most painkillers, such as OxyContin, dissipate from the body within hours. Methadone can linger for days, pooling to a toxic reservoir that depresses the respiratory system. With little warning, patients fall asleep and don’t wake up. Doctors call it the silent death.

In Washington, the poor have been hit the hardest. While Medicaid recipients make up about 8 percent of Washington’s adult population, they account for 48 percent of the methadone deaths.

A case from 2009 epitomizes this divide. Two sisters, injured in a car accident in South King County, needed pain relief. One, with private insurance, received OxyContin, an expensive drug. The other, on Medicaid, received methadone — and within a week, overdosed and died.

“I kept telling her not to go on methadone,” said the surviving sister, who asked that the family’s name not be used, for privacy.

Washington’s methadone death rate ranks among the country’s highest. California, with more than five times the people, has fewer deaths.

But year after year, Washington health officials have proclaimed methadone to be just as safe as any other painkiller. They have disregarded repeated warnings, obscured evidence of harm, and failed to adopt simple lifesaving measures embraced by other states, the Times investigation shows.

Jeff Rochon, head of the Washington State Pharmacy Association, says pharmacists have long recognized that methadone is different from other painkillers. “The data shows that methadone is a more risky medication,” he says. “I think we should be using extreme caution to protect our patients.”

Washington’s methadone deaths tell a story of the politics of health care in a slumping economy. Tight budgets force tough cuts. Often, those hurt the most can afford it least. And often, the suffering is met with silence, with public officials more inclined to rationalize than reckon.

Losing it all

Doctors expected Angeline Burrell’s surgery to be routine. But when Burrell, a 911 dispatcher for King County, had her gall bladder removed in 2004, she was left with excruciating pain, mystifying physicians.

Doctors prescribed painkillers, but the pain wouldn’t go away. The more Burrell sought help, the more doctors suspected she was a pill seeker, a prescription addict scamming for drugs.

“She tried to find a doctor to believe her,” says her mother, Sara Taylor. “She became depressed, and it just kept getting worse.”

Co-workers pitched in, donating sick days to Burrell.

Two years passed before doctors diagnosed surgical-related nerve damage. By then, Burrell had lost her job, her house in Spanaway and her private insurance. She moved into her mother’s home in Renton, destitute and on Medicaid.

Her pain made walking unbearable. She gained weight. Her eyesight dimmed. She spent long hours in bed, reading Patricia Cornwell crime novels, anguishing over her lost prospects of ever becoming a sheriff’s deputy.

The Roosevelt Clinic at the University of Washington Medical Center prescribed drugs for her pain, insomnia, nausea, depression and anxiety, according to medical records Burrell’s family provided to The Times.

“I was so scared about what all the pills were doing to her,” Taylor says.

One of those drugs was methadone.

Federal regulators say it can be dangerous to give methadone to someone on anti-anxiety medications. Burrell was. They say methadone can disrupt breathing and heart beat, especially if a patient has a respiratory disorder. Burrell did. State guidelines warn against giving methadone to someone also receiving other long-acting painkillers. Burrell was.

In early 2008 Dr. Anna Samson doubled Burrell’s methadone dose to 10 milligrams every six hours, according to her medical notes. Samson’s notes also said she would be tapering Burrell off oxycodone, a more expensive painkiller that she began taking while on private insurance. But in the meantime Burrell remained on both.

Samson’s notes made no mention of Burrell’s sleep apnea — involuntary pauses in breathing. Methadone can compound apnea’s effects; federal regulators have tied combining the two to hundreds of preventable deaths.

But Samson’s notes did mention the dangers of Burrell’s pharmacological mix: “I advised her that combinations of these medications can depress her respiratory rate and cause her to stop breathing.”

Samson’s notes were dated Feb. 13, 2008.

Two days later, Burrell was found in a nightshirt, slumped on her bed, arms dangling with open hands. She had stopped breathing, her respiratory muscles paralyzed with stunning speed.

The King County Medical Examiner’s Office found methadone and three other prescription drugs in her body, consumed at normal doses. The medications had combined into a toxic cocktail. The case was ruled an unintended death.

University hospital officials reviewed Burrell’s case and concluded her care was “appropriate,” according to a written statement to The Times.

At age 32, Angeline Burrell became another dot on the map.

The origins of Washington Rx

Starting a decade ago, states discovered a new way to save money on prescription-drug costs, which were increasing about 17 percent a year. All but four created a Preferred Drug List, a register of medications the state will pay for in cases where it covers a patient’s care.

The goal is to steer patients toward less expensive drugs without sacrificing safety; plus, by consolidating purchases, states can often negotiate better deals with drug companies.

Washington’s list took effect in 2004, the year after Gov. Gary Locke signed the state’s new prescription-drug program, Washington Rx, into law.

Often, in state government, the most important decisions get made not by legislators on the House or Senate floor, but by easy-to-miss committees meeting in mundane places. That’s the case with Washington’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee — or P&T committee, for short — a group with enormous influence over patient care.

Under Washington Rx, a P&T committee comprising doctors, pharmacists and other medical experts evaluates drugs in various classes, weeding out any found to be less safe or effective. After that initial cut the state draws up its list, taking into account cost.

No state officials sit on the committee, an arrangement designed to protect the panel’s independence.

But the committee’s members are hand-picked by the three state agencies or programs with a financial stake in the panel’s winnowing process: Medicaid; Labor & Industries, which handles workers’ compensation; and the Health Care Authority, which administers medical benefits for state employees.

Though not committee members, officials from these three entities attend committee meetings and often dominate discussions. With methadone, two doctors in particular — Jeff Thompson, chief medical officer of the Washington Medicaid program, and Gary Franklin, medical director for L&I — have repeatedly deflected concerns about the drug, a review of meeting transcripts shows.

In May 2004, when Washington’s preferred drug list for long-acting painkillers took effect, only two drugs were included: morphine and methadone.

Across the country, 31 states have methadone on their preferred list. But most offer a broad inventory of other pain medications, expanding the options available to physicians, according to a Times survey of these formularies.

Committee meets: 2004-05

To Dr. Stuart Rosenblum, a pain specialist in Portland, what he had to say was worth the six-hour round trip.

In June 2004, Rosenblum drove to the Holiday Inn SeaTac and told Washington’s P&T committee that Oregon had seen a 400 percent increase in deaths associated with methadone. He advised the committee to exclude the painkiller from Washington’s preferred drug list.

“Virtually no response,” he says of the reaction. “It was like, ‘Thanks for testifying.’ “

The committee ruled that methadone was as “safe and effective” as any other painkiller, allowing the state to keep it as a preferred drug.

In June 2005, at the Radisson Hotel near SeaTac, Oregon’s methadone deaths came up again. One member of the P&T committee, Dr. Carol Cordy, asked the right question: “And does Washington have numbers like Oregon?”

But Jeff Thompson, of Washington Medicaid, sidestepped it. He talked about measures the state was taking to address overdoses for painkillers in general — “We’re doing a lot. … In my mind, I think it’s working” — but provided no numbers for methadone-related deaths.

One committee member seemed to think Washington had nothing to worry about, saying: “I know with methadone we don’t really encourage it as a preferred drug.” Citing “issues” with doctors not knowing how to use methadone, she claimed physicians were directed to morphine instead.

Another member wondered if any effort was being made to look at Washington’s methadone overdose rate. But then he dismissed the thought: “Sounds like in our state, methadone’s just not used much. … So it may be just a moot point.”

In fact, the point was anything but moot. Washington’s problems with methadone weren’t minor compared to Oregon’s. Washington’s were much worse.

In 2004, the amount of methadone used in Washington had soared to about 224,000 grams. Oregon, meanwhile, used about 157,000 grams.

While Oregon’s methadone-associated deaths leveled off in 2002, Washington’s became a dramatic fever chart, shooting up. Deaths linked to methadone went from 140 in 2002, to 166 in 2003, to 256 in 2004, according to a Times analysis of death certificates. Oregon, by comparison, had 99 deaths in 2004.

Washington’s deaths were among the highest in the country — surpassed, in 2004, by only North Carolina and Florida, both more populous states.

In May 2005, the month before the meeting at the Radisson, 28 people in Washington died from poisonings linked to methadone. They included a 30-year-old nursing assistant from Spokane, a 43-year-old waitress from Puyallup and a 44-year-old welder from Vancouver.

The day after the committee met, a 38-year-old database specialist from Shelton who was on both methadone and antidepressants overdosed and died.

A methadone primer: cheap but complex

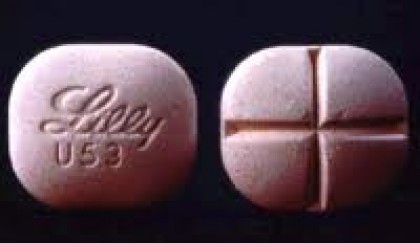

For decades, methadone — a synthetic opioid developed in the 1930s by a German company — was associated not with pain relief but with weaning addicts off heroin and other drugs. The word summoned an image of clinics, often in seedy parts of town.

But when the medical community’s philosophy on pain shifted, so did its take on methadone.

As recently as the mid-1990s, Washington discouraged doctors from prescribing narcotic painkillers to noncancer patients. Pain was considered a symptom, not an ailment. But in the late ’90s, as patients protested, the health-care system switched course, viewing untreated pain as unnecessary suffering. By 2001, the nation’s top hospital-accreditation agency mandated treatment of pain.

In this new environment, methadone emerged as an attractive option. Less than a dollar a dose, the drug was three to four times cheaper than its closest competitor and 12 times cheaper than brand-name OxyContin.

From 1999 to 2005, the use of methadone in the United States went from 965,000 grams to 5.4 million grams, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

But then there are the drug’s complicating factors.

While the pain relief from methadone might last four to eight hours, the drug’s half-life can extend for days. Various studies have placed the high end at 59 hours, or 91 hours, or even 128 hours. That means the drug’s dangers — mainly, its effect on the respiratory system — last long after its benefits have worn off. A patient in pain might be tempted to take another pill without being aware of the toxic buildup.

Most prescription drugs harbor risks when mixed with alcohol or other medications. Methadone can be particularly hazardous when combined with drugs called benzodiazepines, used to treat anxiety disorders.

Patients struggling with pain often become depressed or anxious, doctors say, making this risk factor a critical one. For 2009, The Times documented 274 methadone-related deaths in Washington. Death certificates show that 119 patients, or 43 percent, also consumed prescription medications for anxiety or other mental-health disorders.

In its regulation of addiction clinics, the federal government has long recognized methadone’s dangers. Under the mantra “start low, go slow,” federal law requires tight controls. Addicts, for example, must visit the clinic daily at the beginning of treatment. That’s because the drug’s effects on individuals can vary dramatically.

But with pain patients, many doctors prescribe a month’s worth of methadone, with little or no follow-up.

As the use of methadone has climbed, so have the overdoses. From 1999 to 2005, methadone-associated deaths in the United States climbed from 786 to 4,462, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of course, not all those deaths can be attributed to prescribing practices. Some overdose victims obtain methadone without a prescription or combine it with illegal drugs such as cocaine. The Times found that up to 20 percent of methadone-related deaths in Washington involved a combination with illicit substances, suggesting the overdoses were a byproduct of abuse.

In November 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration sounded an alarm about methadone, following an investigative report in a West Virginia newspaper, The Charleston Gazette. The FDA lowered its dosage guideline for methadone and issued a public-health advisory with this headline: “Methadone Use for Pain Control May Result in Death and Life-Threatening Changes in Breathing and Heart Beat.”

Committee meets: 2006

Once again, committee member Carol Cordy asked the right question.

When the P&T committee met in December 2006 at the Seattle Airport Marriott, it had been three weeks since the FDA issued its methadone alert. Cordy, a family physician in Seattle, brought up methadone and morphine — the state’s choices as preferred painkillers — and asked: “Has there been any increase in accidental overdoses?”

Gary Franklin, L&I’s medical director, cited a study of workers’ compensation recipients that found 32 overdose deaths between 1995 and 2002. “They were half methadone and half oxycodone,” Franklin said.

But those numbers didn’t answer Cordy’s question. The L&I study applied only to a small population. More important, its time span preceded the start of Washington’s preferred drug list. “No,” Cordy said. She wanted to know about any increase after 2003.

“Yeah, I guess we haven’t looked at that,” Franklin said. He kicked the question to L&I’s pharmacy manager, who talked up the challenges of doing such analysis, saying death certificates often list more than one drug: “So it’s kind of hard to divvy out, you know, the particular.”

Cordy’s question was not an impossible one to answer. The state Department of Health analyzes death certificates and reaches conclusions even when multiple drugs are listed. The Times did the same and found these numbers: In 2003, the year before the preferred drug list took effect, the state recorded 166 deaths linked to methadone; by 2006, that number had more than doubled, to 342.

Just as telling, those 342 deaths were three times the number attributed to any other long-acting painkiller.

Cordy wasn’t the first to question methadone in 2006. A doctor from the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, Dermot Fitzgibbon, appeared at a P&T committee meeting that summer and urged the state to offer more choices than methadone and morphine, calling methadone “particularly problematic.” But Washington refused to change course.

At the end of the December 2006 meeting, Siri Childs, pharmacy administrator for Washington Medicaid, told the committee what she called a “good story.”

“Do you all want me to tell you how many OxyContin users we have in Washington nowadays?”

“Sure,” came the answer.

“You’re going to be just amazed, because when we started the preferred drug list with the long-acting opioids, OxyContin represented 70 percent of our utilization. Today … we’re down to less than 3 percent.”

Washington’s death toll from methadone was soaring. But the state was realizing its goal of moving people off more expensive painkillers.

‘Very little data’

In evaluating drugs for safety and effectiveness, the P&T committee is required to rely on the best available science. To find it, the state hired Oregon Health & Science University, a teaching hospital and research center based in Portland.

The OHSU researchers collect and analyze medical studies, looking for the best clinical trials, ones that compare drugs head-to-head and are randomized, controlled and of long duration.

In the case of long-acting opioids, however, researchers have had only a few studies of poor or fair quality to consider.

At a P&T committee meeting in 2005, Dr. Roger Chou of OHSU told members there is “a continued lack of good study on methadone.” In 2006 he said, “There’s no evidence that one long-acting opioid is superior to others,” to which the committee’s vice chair said, “Thank you, Roger, that was excellent.” In 2008 Chou said, “We really have very little data on methadone’s use.”

In the absence of top-notch clinical trials, Washington officials adopted the position that methadone is just as safe and effective as other drugs in its class.

Franklin, the L&I medical director, told The Times that “if it wasn’t methadone killing people” in Washington, it would be another long-acting painkiller — oxycodone or fentanyl or something else. He said prescribers and patients have become too quick to turn to long-acting painkillers in general, a shift fueled by “weak science” and support from the pharmaceutical industry.

“The overall problem — the public-health emergency in this country — is a dosing problem,” Franklin said. “It is not a methadone problem.”

Thompson, the Medicaid chief medical officer, said: “If you’re looking for a single villain, you could make methadone that villain. But I think it’s more complex than that.”

Methadone, he said, “is a safe drug if used correctly. … If it’s an unsafe drug, why have we been using it for 40 years?”

For Washington, the preferred drug list has yielded financial rewards. In fiscal year 2008, the Medicaid program’s estimated savings came to $45.5 million, according to an audit by the state’s Joint Legislative Audit & Review Committee. Looking only at long-acting opioids — the class with methadone — that year’s savings amounted to $3 million.

Some other states, meanwhile, have treated methadone’s mortality figures and complex properties as sufficient grounds to urge caution.

New York issued a health advisory in January 2009 about methadone’s dangers. Five months later, Oregon alerted doctors that methadone’s “safety is of increasing concern,” and the drug “should not be considered a first-line agent.”

Fifteen states have left methadone off their preferred drug lists, despite its low cost. North Carolina, like Washington, has consistently ranked among the top five states in methadone-associated deaths. When North Carolina adopted its first preferred drug list last year, the state rejected methadone.

North Carolina had analyzed the drug’s toll and did not want to “encourage its use,” said Dr. Lisa Weeks, chairwoman of the state’s Preferred Drug List Review Panel.

Committee meets: 2009

“Quite frankly, I’m at a loss of what to do,” Thompson told the committee at its February 2009 meeting.

His consternation traced to a recent Department of Health study that produced some alarming numbers about Medicaid.

Analyzing all prescription-opioid fatalities in Washington from 2004 to 2007, department researchers discovered that a stunning 64 percent involved methadone.

And of the people whose deaths were linked to methadone, 48 percent were on Medicaid.

The findings highlighted methadone’s “prominence” in opioid overdoses, the Health Department study said, and indicated “the Medicaid population is at high risk.”

“I think this is a distinction that we don’t want, and it just keeps growing,” Thompson said of the Medicaid population’s disproportionate share of the state’s prescription-drug deaths.

In medical circles, the department’s findings about methadone and Medicaid broke new ground. In the fall of 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — the federal agency assigned to protect public health — published the study in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

But in Washington, state officials have done little to spread the word.

When the P&T committee met in December 2009, Bill Struyk, a pharmaceutical representative, brought up “Generic News,” a newsletter produced by state Medicaid officials for health-care professionals. He said the newsletter told only half the story of methadone: Officials publicized how cheap it was, without saying how many deaths it was linked to.

“Without disclosure of that fact, are we making informed decisions?” Struyk asked.

Thompson jumped to methadone’s defense, pointing to other drugs — for example, ones used in mental-health treatment — also linked to fatal overdoses. The state should be “very careful” about “picking on a drug,” he said.

“If you look at the dangers, it’s not just methadone,” Thompson said.

How about a note, Struyk suggested, advising methadone prescribers to be cautious?

“It’s not only due just to methadone,” Thompson said.

“No,” Struyk said. “But 64 percent are.”

Thompson said he would include methadone’s toll in a future newsletter. “Because it is important,” he said. But he never did.

Alarmed by the Health Department study, state officials launched an internal monitoring program to track practitioners who prescribe high volumes of narcotics to Medicaid patients, Thompson told The Times. In addition, the state now educates hundreds of Medicaid patients on the risks and use of potent painkillers.

One of the state’s broadest initiatives to save lives, Thompson said, is a “lock-out” program that requires about 3,800 Medicaid patients to use only one practitioner for prescriptions in order to avoid “doctor shopping.”

‘Elephant in the room’

In December 2010, Dr. Michael Schiesser, a pain specialist in Bellevue, wrote a letter to the P&T committee, retracing the state’s history with methadone and crying foul.

When it comes to methadone, Schiesser is the closest thing the state has to a whistle-blower. Three years ago he joined a Health Department work group on accidental poisonings. After that he became involved in legislative deliberations about pain management.

He reviewed transcripts of P&T committee meetings and swept up reports about methadone. The more research he did, the more troubled he became.

Schiesser uses the word “creep” to describe methadone’s grip on Washington. As more years passed with the P&T committee saying the drug was as safe as any other, the harder it became for the state to reverse course or hedge by issuing special alerts to physicians of potential complications with methadone.

“So you start to ignore the elephant in the room, which is the mounting evidence,” Schiesser says.

His letter challenged a 2008 report that Oregon Health & Science University provided to the committee, saying it “contains errors, deficient logic, and relevant omissions.”

The report said one study “found no differences” between methadone and other drugs for overdose risk, when, in fact, the opposite was true, Schiesser wrote. The report mentioned a “black-box warning” from the FDA about OxyContin but not one from the same agency about methadone, he wrote.

In a written reply, an OHSU doctor downplayed Schiesser’s points, saying, for example, that FDA black-box warnings are “not evidence.”

To Schiesser, such hyper-selectivity has allowed the state to keep saying there’s no evidence of methadone being especially risky — and to the state, no news is good news. He describes the result as: “Because we don’t know, therefore it ain’t so.”

In Washington, medications can go on and off the Preferred Drug List as more evidence develops. The P&T committee meets later this month, when its members will evaluate — once again — the safety of methadone.

Database reporter Justin Mayo and news researchers David Turim and Gene Balk contributed to this report. Michael J. Berens: 206-464-2288 or mberens@seattletimes.com; Ken Armstrong: 206-464-3730 or karmstrong@seattletimes.com

New pain-management law leaves patients hurting

It was meant to curb rising overdose deaths. But Washington’s new pain-management law doesn’t specifically address methadone —

by far, the state’s number-one killer among long-acting painkillers. The law also makes it more difficult for doctors to treat pain, causing many to stop trying, leaving legions of patients without life-enabling medication.

Pain clinic leaves behind doubts, chaos and deaths

The Vancouver clinic’s high doses — “Take 10 every 6 hours,” one painkiller prescription said — reveal murky regulations and Washington state’s anemic response.