Drug War

By Robert Perkinson. The Drug Enforcement Administration Museum and Visitors Center may be America’s most uninspiring attempt at war commemoration.

By Robert Perkinson. The Drug Enforcement Administration Museum and Visitors Center may be America’s most uninspiring attempt at war commemoration.

Its low-budget displays, stuffed into a sterile building near the Pentagon, strive for a good-versus-evil story line but exude uncertainty. Snapshots of officers atop piles of impounded narcotics fail to convey the urgency of battle.

Confiscated drug paraphernalia showcase wily ingenuity as much as social menace. But across the Potomac, next to Congressional Cemetery, rises a more fitting tribute to the “war on drugs”: Washington’s city jail, through which 18,000 inmates pass each year, 89 percent of them black and three-quarters of them incarcerated for nonviolent of fenses. With its X-shaped towers surrounded by razor wire, the sprawling complex devours resources but, most criminologists agree, does comparably little to protect the public. It stands as a monument to punitive government bloat.

Now four decades old, America’s drug war, initiated in its modern form by Richard Nixon, has burned through $1 trillion and helped make the United States the most locked-down country on earth. Yet victory still recedes from view. In 1970, some 20 million Americans had experimented with illegal drugs; by 2007, 138 million had. While drug purity has increased, street prices over the long term have dropped — precisely the opposite trajectory promised by drug warriors. Small wonder that a growing number of skeptics, from George Will to George Soros, have called for a serious change of course.

With a new regime in Washington, led by a president who admits to having used cocaine in his youth and a drug czar who rejects martial metaphors, this is a good time to look back on America’s first “war without end” and its pre-eminent target, as the documentary filmmaker Tom Feiling does in “Cocaine Nation.”

An impassioned and wide-ranging if occasionally jumbled survey of “the white trade” and its enemies, Feiling’s book (published last year in Britain as “The Candy Machine”) begins with the extraction of the ancient coca leaf’s most potent alkaloid, cocaine, in the mid-19th century. Possessing wondrous qualities — a pharmaceutical company boasted that cocaine could “make the coward brave, the silent eloquent, and render the sufferer insensitive to pain” — the product swept the globe as an additive to medicine, wine (Ulysses S. Grant was an early quaffer) and, of course, Coca-Cola, whose red and white colors, Feiling writes, pay homage to the Peruvian flag.

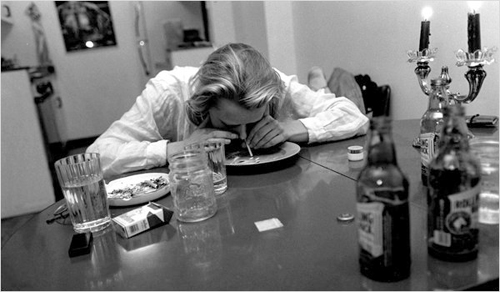

This initial cocaine craze petered out in the first half of the 20th century, in the wake of pharmacy regulation, drug control protocols and consumers’ second thoughts. But another, larger wave rose in the 1970s, as hedonists from Hollywood to Wall Street turned cocaine into “the Champagne of drugs,” as The New York Times declared in 1974. Because most users of the stimulant never became addicted, and because they had “upper-class cachet,” Feiling notes, its resurgence was at first greeted with a shrug by government. Gerald Ford’s White House observed that cocaine “does not usually result in serious social consequences, such as crime, hospital emergency room admissions or death.”

But when suppliers introduced a down-market product, crack cocaine, in the 1980s — “cocaine for poor people,” as one dealer described it to Feiling — social panic ensued. Crack is pharmacologically identical to powder cocaine, but its smokable rocks produce quicker, more intense highs (and harder falls). Attracting legions of users in decaying urban centers, it contributed to property crime, child neglect, homicidal turf battles and, not least, political reaction. Brandishing a bag of crack in the Oval Office, the first President Bush called illegal drugs “the gravest domestic threat facing our nation.” No-knock police raids and mandatory minimum sentencing followed. The drug war became total war, overstuffing jails and exacerbating racial inequality but failing to create a “drug-free America.”

This domestic tale of destruction has been well chronicled by journalists, social scientists and addicts-turned-memoirists. What sets Feiling’s book apart is his analysis of how America’s insatiable appetite for narcotics and its zealous determination to quash those cravings have spread misery and violence across the globe.

During cocaine’s postwar renaissance, mafiosi based in Cuba met demand in the United States, the world’s largest cocaine market. But after the revolution, coca capitalists dispersed, chartering new organizations, establishing new labs and supply lines, and demonstrating remarkable adaptability in response to law-enforcement pressure. Production shifted from Peru to Bolivia to Colombia, and is now shifting back to Peru. Snuffed out in one area, cocaine surges in another.

Feiling vividly describes the supply side of the cocaine business, which, he argues, “thrives on the poverty not just of individuals and communities, but of governments.” In Colombia, which remains the world’s leading producer of cocaine despite the $5 billion in anti-narcotics and counterinsurgency aid the United States has fed into the country since 2000, Feiling profiles campesinos in the rural Putumayo district whose primary source of income is coca, although they receive relatively little for their crops.

In a region where markets are distant, roads are poor and the prices for legal produce like yucca and plantains are low, the coca farmers “become slaves of the mafia,” a Colombian congressman tells Feiling — the rural correlates of low-level street dealers in America who risk death and imprisonment to earn “roughly the federal minimum wage.” At the top of the cocaine hierarchy, drug barons make millions, but their careers tend to be short, their fortunes soaked with blood. Because of the violence perpetrated by traffickers and insurgents, and the more pervasive violence committed by right-wing paramilitaries and the government, Colombia’s population of internally displaced people ranks second only to Sudan’s.

As radar surveillance has pushed smuggling routes from the sky and sea to the land, the drug war’s front lines have moved to Mexico, where trafficking- related violence has claimed more than 22,000 lives since 2007. Although the Mexican government’s latest offensive may yet constrict supply, curtail corruption and reduce rather than provoke carnage, the length and complexity of the United States-Mexico border (and the money to be made breaching it) presents a daunting challenge. “Americans consume roughly 290 metric tons of cocaine a year,” Feiling writes, a load that “could be carried across the U.S.-Mexican border in just 13 trucks. Instead, it seeps in in thousands of ingenious disguises.”

Although Feiling doesn’t soft-pedal the harm of drug dependence — to addicts, mainly, but also to their families and communities — he argues convincingly that the remedy promoted most aggressively by the United States has proved far worse than the disease. As an alternative, he develops a lengthy brief for a solution he admits stands little chance of implementation: legalization. There would be costs, he acknowledges, including, perhaps, wider experimentation and addiction, but he contends that restrictions on marketing, elevated vice taxes and a proliferation of treatment beds instead of jail cells could hardly fail more spectacularly than has prohibition. Hard as it is to imagine, the least ruinous solution to the white scourge may be the white flag of surrender.

Robert Perkinson is the author of “Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire.”

The New York Times

Aug 1, 2010

Copyright © 2010, The New York Times Company