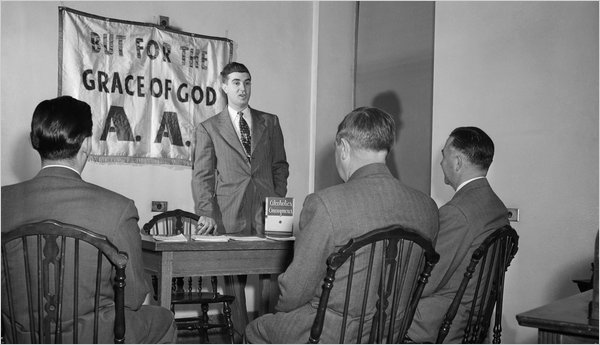

in A.A.

Challenging the Second ‘A’ in A.A.

Challenging the Second ‘A’ in A.A.

By DAVID COLMAN

I’M David Colman, and I’m an alcoholic.

In the 15 years since I quit drinking, I’ve neither spoken nor written those words, and now, in doing so, I have more or less violated the first-name-only tenet of Alcoholics Anonymous, the grass-roots organization whose meetings have helped me (and millions of others) quit drinking. As A.A.’s 11th Tradition states, “We need always maintain personal anonymity at the level of press, radio and films.”

Of course, in the meetings I’ve attended over the years, anonymity has always been a kind of collective fiction. Before and after sessions, I find myself talking to people I know from work: greeting an artist I’ve interviewed or a fashion designer I want to; hashing over logistics with a P.R. guy or a magazine editor.

At one of these, a big Sunday meeting in Greenwich Village, I’ve been surprised to see well-known actors and authors up on the dais to share their stories — often, I’ve noticed, when they have something to promote, as if it’s just another a stop on the press tour. Frequently, I find friends introducing me to others in the group by my full name, “You know David Colman, don’t you?”

More and more, anonymity is seeming like an anachronistic vestige of the Great Depression, when A.A. got its start and when alcoholism was seen as not just a weakness but a disgrace.

Over the past few years, so many memoirs about recovery have been released that they constitute a genre unto itself. (Kick Lit?) Moreover, many of them share a format that comes from A.A. itself: most 12-step meetings revolve loosely around what is called a “qualification” — an informal monologue by one member about his or her battle with the bottle.

The last few years have brought us fleshed-out qualifications by Augusten Burroughs (“Dry”), Mary Karr (“Lit”), Nikki Sixx (“The Heroin Diaries”), Eric Clapton (“Clapton: The Autobiography”), Nic Sheff (“Tweak”) and James Frey (“A Million Little Pieces,” fabricated, in part, though it was), as well as hundreds of other blurry, cautionary tales of debauchery and redemption.

Somewhere, their patron saint — Augustine of Hippo, whose “Confessions” inaugurated the sinner-cum-saint format in A.D. 398 — is smiling. With precious few exceptions, like Thomas De Quincey’s “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater” in 1822 and Lillian Roth’s “I’ll Cry Tomorrow” in 1954, the form barely existed 20 years ago.

People seeking help from any number of addictions can find public role models — the quitterati, if you will — like Eminem (the album “Recovery”), Pink (the song “Sober”), and Russell Brand, in the remake of “Arthur” (if they were among the few moviegoers who actually saw it), which seemed in many ways to echo the now-abandoned life he wrote about in “My Booky Wook: A Memoir of Sex, Drugs and Stand-Up.”

“I think it’s extremely healthy that anonymity is fading,” said Clancy Martin, a professor of philosophy at the University of Missouri at Kansas City.

Mr. Martin broke his anonymity in a 9,000-word essay he wrote in the January issue of Harper’s Magazine detailing his experience getting sober in A.A. and his frustrations with the resistance he met in meetings when trying to talk openly about the psychiatric medications that he, like many recovering addicts, took.

But not everyone is happy about this turn toward openness, chief among them A.A. itself, which last year issued an expanded statement on anonymity that has been read at some meetings, adding language about the importance of discretion on social networking Web sites, hoping to ward off breaches both purposeful and accidental.

Some people have posted pictures taken at A.A. meetings on their Facebook pages, said a spokeswoman for A.A. who asked not to be identified. In some cases, they may have involuntarily outed other attendees. “We don’t have the wherewithal to deal with the complaints,” she added. “It’s literally in the thousands now.”

IN the world of recovery — encompassing the greater community of recovering addicts, which overlaps mightily but not officially with A.A. and its alphabet soup of sister groups — anonymity is a concept that, even if it doesn’t feel bit old-fashioned, can be self-defeating.

“Having to deny your own participation in a program that is helping your life doesn’t make sense to me,” said Maer Roshan, the editor of The Fix, a new, hip-feeling Web magazine aimed at the recovery world. “You could be focusing light on something that will make it better and more honest and more helpful.”

The idea for The Fix — a mixture of serious journalism, reviews of rehab programs and irreverent features (like one about the “most irritating” 12-step slogans) — came to Mr. Roshan about 18 months ago, when he was living in Los Angeles and out of rehab for alcohol and drug use. Newly exposed to the realm of recovery, Mr. Roshan was struck by how little solid and comprehensive information there was about it.

“There are hundreds of books and millions of Web articles, but it’s hard to discern what’s real and what’s agenda,” he said. “It’s so weird. With Yelp, you can find out everything about the pizza place on the corner, but there’s no good, unfiltered, reported information on most rehabs — and this is something you could be spending $100,000 on.”

Having started an early mainstream-style gay and lesbian magazine in the early 1990s — the short-lived QW — Mr. Roshan was also struck by the similarities between the two worlds, particularly when it came to the issue of anonymity.

“The recovery world is now where the gay world was then,” he said. “Back then, there was a still a stigma to saying you were gay.

There was a community, but it was mired in self-doubt and self-hatred, and it’s changed considerably. Not just gay people, but the perception of gay people has changed. There’s a lot of secretiveness and shame in the recovery world, too, but that’s changing.”

“There’s not a day that goes by that some major figure doesn’t announce himself as a substance abuser. There’s a community of people who don’t see it as shameful. These are people that have learned from challenges who have a hunger for life and money to spend, and who want to make up for lost time.”

But even for people who want to be more open, the exact line of where anonymity begins and ends is not clear-cut. Many people assume that to identify themselves as “sober” or “in recovery” qualifies as a breach. In fact, only identifying yourself as a member of A.A. or other specific 12-step groups does.

The topic of clarifying these boundaries was brought up yet again at A.A.’s annual General Service Conference, which took place in New York City last week, with debate focused on how the organization’s “Understanding Anonymity” pamphlet could be best worded to guide those who want to follow the letter or spirit of the principle.

This delicate question was the subject of an essay by Susan Cheever in The Fix, titled “Is It Time to Take the Anonymous Out of A.A.?” Given that she has written books about both her alcoholism and that of her father, the writer John Cheever, as well as one on the history of A.A., it’s not hard to guess whether she is an A.A. member. But in her essay, she vented her frustrations with trying to observe the practice of anonymity while trying to speak frankly about addiction.

“We are in the midst of a public health crisis when it comes to understanding and treating addiction,” Ms. Cheever wrote. “A.A.’s principle of anonymity may only be contributing to general confusion and prejudice.”

Her message wasn’t exactly greeted with open arms, inciting a flood of largely critical comments from the site’s readers. (One of the tamer ones: “Without ANONYMITY, A.A. will not continue to exist and help millions of alcoholics and addicts all over the world!”)

Still, others have embraced the path of full disclosure and been rewarded. Since becoming sober in 2006, Patrick J. Kennedy, the former Rhode Island congressman and a son of the late Edward M. Kennedy, has acknowledged that he attends A.A. meetings while also actively campaigning for legislation to make addiction be held to the same standard of insurance coverage as other mental health issues. (The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, included as a rider on the Troubled Asset Relief Program, was signed into law in October 2008.)

“The personal identification that Jim and I brought to this issue as recovering alcoholics gave us a place from which to speak about this,” Mr. Kennedy said, referring to former Representative Jim Ramstad, Republican of Minnesota, his co-sponsor of the bill (and for a time, his sponsor in A.A.). “Stigma here is our biggest barrier, and knowledge and understanding are the antidote to stigma.”

Molly Jong-Fast, 32, a New York novelist who became sober in A.A. 12 years ago, agrees. “It’s seems crazy that we can’t just be out with it, in this day and age,” Ms. Jong-Fast said. “I don’t want to have to hide my sobriety; it’s the best thing about me.”

Some are trying to find a middle ground between secrecy and full disclosure. Faces and Voices of Recovery, a group based in Washington, has recruited people to speak publicly about being sober while nominally retaining their anonymity, a process they call “recovery messaging.” Their goal is to stress the positive aspects of sobriety and counter negative public perceptions of recovered addicts and alcoholics.

“I remember growing up, if you saw someone on TV who was in recovery, you couldn’t see their face or their voice was disembodied,” said Pat Taylor, the group’s executive director.

“But there’s nothing that prohibits people from talking about recovery as long as they don’t mention their actual support group. And the other thing is that there are so many ways that people are getting into recovery and sustaining it. It’s not just one path.”

In the professional recovery world, where one might expect to find a consensus, the debate can be the fiercest of all.

Some believe that more people in recovery should go public. “I violate my anonymity daily,” said Rick Ohrstrom, the chairman of C4 Recovery Solutions, a consultancy firm. “I am 25 years in recovery, and have been out there fighting for the rights of people in recovery, and I’m sick and tired of people in A.A. meetings not lifting a finger to do anything about it. They hide behind anonymity — if you don’t tell anyone else that recovery works, that’s what you’re doing. That’s not how A.A. got to be where it was.”

Others insist on the importance of privacy. “Our effectiveness to reach the still-suffering alcoholic is better protected by anonymity, even today, than not having anonymity at the public level,” said Dr. Andrea Barthwell, the chief executive of Two Dreams Outer Banks, a rehab center in Corolla, N.C. “It’s possible that anonymity would be lifted sometime in the future, but there’s no one that’s made that compelling argument yet — and it can’t be done from outside the fellowship.”

But even some who have faithfully observed the practice, myself included, have a suspicion that, if staying anonymous is not an outdated (and sometimes absurd) technicality, it is at least a choice that everyone should have.

“I am increasingly uncomfortable with this level of dishonesty,” Ms. Cheever said in a telephone interview last month. “This dancing around and hedging, figuring out ways of saying it that aren’t really saying it, so that people in recovery know what I am talking about — all the code words. I am sure this is not what Bill intended.”

Having written a biography of Bill — that is, Bill Wilson, one of the founders of A.A. — Ms. Cheever is in a position to say what the idea of anonymity was intended to do as few are. First and foremost, anonymity was meant to shield those struggling to become sober from the stigma of being an alcoholic, a stigma far more marked 75 years ago when there was little research on alcoholism as a medical condition over which its sufferers had little control.

These are the most common considerations when weighing the reasons for anonymity. But the second part of the ideal, spelled out in A.A.’s 12th Tradition, makes the case for observing anonymity within A.A. itself — and it’s worth noting that there’s little, if any, dissension on this subject.

Unlike the more practical 11th Tradition, aimed at the outer world, the 12th Tradition takes a crack at our far more problematic inner world. Stating (somewhat obliquely) that “anonymity is the spiritual foundation of all our traditions, ever reminding us to place principles before personalities,” it’s about cultivating the often overlooked idea of humility, an excellent means for quieting the now-me-more urges that bedevil addictive people more than their peers.

In this light, anonymity is a token, a symbolic gesture, but we are symbolic people. Even shedding your last name can go a surprisingly long way toward shedding the weight of being yourself.