binge drinking

Scientists try to assess the impact of binge drinking on the brains of teens.

Scientists try to assess the impact of binge drinking on the brains of teens.

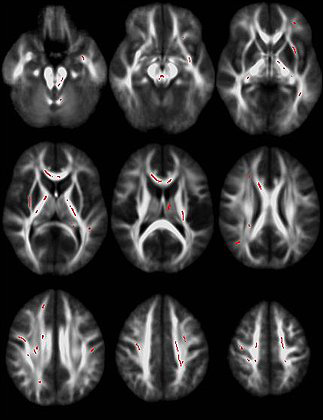

Darkened areas highlight where binge drinking adolescents had altered white matter on the brain from the control group.

Photo Credit: Susan Tapert Photo.

By Laura Hambleton. Special to The Washington Post. Monday, December 6, 2010; 1:27 PM

Emergency room nurse Sheila DeRiso stood at the front of the high school auditorium and looked out on her audience of 50 teenagers and parents. From a black nylon bag she pulled out a long, plastic tube, then a stomach pump, a speculum, a catheter and an adult diaper. The group tittered. All these items are used in the ER every day to treat binge-drinking teens, she told them.

Then she yanked out a white body bag and unfolded it: “And this is if you don’t make it.”

The audience was dead silent.

Binge drinking, or consuming many drinks fairly quickly, has been a hallmark of college life. But students in high school and even middle school are also engaging in it, according to DeRiso, local police officials and experts. In one 2005 study of 5,300 middle school students, about 8 percent of seventh-graders and 17 percent of eighth-graders said they had tried binge drinking during that year.

The results of these bouts of excessive drinking show up in ERs across the region. Most weekend nights – and especially around holidays – young people arrive at the ER injured in car crashes, sick with alcohol blood poisoning, unconscious or barely conscious after binge drinking or engaging in the newest trend of blackout drinking, or drinking to the point of intentionally passing out.

“I am a nurse,” DeRiso told her audience at Magruder High School in Rockville. “Alcohol affects your thinking, your coordination and judgment. Alcohol affects your brain.”

Exactly how it affects the fast-developing and still malleable brains of young people is a hot scientific question. At a time when binge drinking is an entrenched part of life for many young people, scientists and epidemiologists are looking beyond the bodily injury that DeRiso sees in the ER at Montgomery General Hospital in Olney to the cognitive damage and physical and chemical changes that heavy drinking can cause in the adolescent brain.

Teens consuming alcohol

First, consider these statistics:

l Nationwide, people ages 12 to 20 drink 11 percent of all alcohol imbibed in the United States each year – and more than 90 percent of that is consumed in the form of binge drinks, according to a 2008 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

l Nearly half of Maryland high school seniors say they have tried binge drinking, according to a study published in 2008 by the Maryland State Department of Education. A 2009 report that looked at students in all high school grades found that one in five said he or she had “had five or more drinks in a row within a couple hours on at least one day” in the preceding month.

l In Virginia, 76 percent of high school seniors and 64 percent of 10th-graders reported using alcohol in the previous 30 days, according to an annual youth study published in 2006.

l In 2005, 1,825 college students ages 18 to 24 died from alcohol-related unintentional injuries, including car crashes, or about five every day, one every five hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

l Although binge drinking is often defined as men downing at least five drinks or women four within two hours, a 2006 study of more than 10,000 first-semester freshmen at 14 colleges found that about 20 percent of men had had 10 or more drinks at one sitting and 10 percent of women had downed eight or more at least once during the previous two weeks.

“I’d guess that at least a third of the patients who arrive [in the ER] between midnight and 5 a.m. are intoxicated,” said Mary Pat McKay, a George Washington University professor of emergency medicine and public health who works in the ER at GWU Hospital. Many of the patients are university students, she said. “Holiday weekends and weekends after midterms tend to be the worst.”

An adolescent brain

What are the consequences of so much drinking when your brain is still developing?

According to scientists, a young brain is incredibly dynamic, creating a multitude of connections among neurons, or brain cells, as a child is exposed to new things every day and learns new skills. Around 12 years old, the brain begins to refine those connections, in a “use-it-or-lose-it” process scientists think involves a kind of pruning, where only the most vital and exercised connections remain.

“There’s a lot of chatter going on in the brain with all those connections,” said Duke University professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences Scott Swartzwelder, an author of the 2006 study of binge drinking among college freshmen. “Some of them are unnecessary. I liken it to a marble sculpture: When you chip away the extraneous connections, you reveal what the image really is. The remaining connections become more efficient. You begin to think through things without getting distracted. You begin to think more clearly.”

Enter alcohol – large quantities of alcohol – which is a powerful drug that passes quickly into the bloodstream through the stomach and small intestine and makes its way to every organ of the body, including the brain.

“It is a very potent depressant that goes everywhere and affects every system,” said Marc Schuckit, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California at San Diego and editor of the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. “It affects every neurochemical system in the brain.”

For instance, scientists believe alcohol can trigger an increase in dopamine, a chemical associated with pleasure and reward. They believe alcohol disrupts the workings of the frontal lobe, important in coordinating brain functions and modulating reasoning, intelligence and impulses. And since the first drink was consumed centuries ago, people have written about alcohol’s ability to interrupt memory and learning, Swartzwelder said.

“Those three systems – learning, reward and the frontal lobe – are areas alcohol can powerfully affect,” especially in a brain that is still a work in progress, said Swartzwelder, who has been studying this process in adolescent rats.

The memory deficit

Swartzwelder specifically studies the hippocampus, the part of the brain dedicated to forming memories and learning skills. Because the human hippocampus is similar in structure to a rat’s, Swartzwelder has studied rats roughly the comparable age of adolescents and found that large quantities of alcohol can stop the hippocampus from functioning properly.

In humans that is called blackout drinking; in rats Swartzwelder calls it a profound memory deficit. It works like this: A teen drinks heavily but continues to function and doesn’t lose consciousness. But the next day he or she cannot remember a thing that happened. The hippocampus stopped encoding new memories during that blackout time, according to Swartzwelder.

Swartzwelder gives his rats a dose of alcohol, and then “we teach them to go through the maze. And then see how they do.’‘

Not very well, apparently, which probably has implications for humans. If a student studies math problems all day and then drinks to the point of blacking out that night, chances are he will have to relearn all those problems once the alcohol has left his system, Swartzwelder said.

“People joke about blackouts, but they represent a serious neurological insult,” he said. “If you took a blow to the head hard enough to disrupt memory, you’d be really worried.”

Swartzwelder has looked for a biological explanation for the alcohol-fueled impairment of the hippocampus. He has extracted that part of a rat’s brain and given it enough oxygen, glucose and other fluids to mimic ordinary life. He then adds alcohol and measures the electric currents in those brain cells. “Cells start to quiet down and the circuits stop responding,” he said.

Swartzwelder cannot say whether alcohol-fueled deficiencies in learning and memory will persist, but another study he’s done is suggestive. He compared adult rats that had been given alcohol during adolescence with adult rats that had never been given it. When both were then exposed to alcohol, the first group was more resistant to alcohol’s sleepiness effect – an effect that naturally can limit alcohol consumption – and they also showed more impaired learning and memory skills.

This suggests, he said, that “you are changing the wiring of the brain with repeated alcohol exposure during adolescence.”

Michael Taffe, an associate professor at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif., has also looked at the structure of brains exposed to alcohol and found a slowing in the growth of brain cells that transmit signals.

Taffe analyzed two groups of monkeys, one given an alcohol-Tang mixture to drink and one just plain Tang. He then tested how well each group could learn, remember and repeat a pattern on a touch-screen computer test. The group fed the alcohol could follow the pattern for five seconds before falling off in accuracy; the non-alcohol group lasted 20 seconds. Taffe then looked at the brains of these monkeys and found that the heavy drinkers had made fewer new neurons.

“We think there is a connection between the hippocampus and different kinds of memory tasks,” Taffe said. “We think there is likely neurobiological damage, and what we saw is plausibly related to behavioral changes.”

Dings in white matter

Eight years ago, Susan Tapert, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California at San Diego, started following a group of 28 people who were then 12 to 14 years old. Half had already engaged in binge drinking and half had not. For her study, Tapert each year took MRI scans of the brains of both groups and had the two groups take various cognitive and skill tests.

Among the drinkers, Tapert began to find small abnormalities in their MRIs that looked like ding marks in their brain’s white matter – on the fatty myelin coating of the axons, the connecting fiber between neurons. Axons allow messages to flow to and from neurons, and the insulated myelin coating speeds the transmission. So if the myelin is compromised, Tapert hypothesized, students wouldn’t perform as well on cognitive and memory tests. That turned out to be the case.

“We’re seeing reduced quality of white matter in adolescents who engage in heavy drinking,” she said. “White matter is important for cognitive abilities. The more these axons are coated with myelin, the more efficiently information is relayed.”

“Alcohol is linked consistently with poor performance on a range of tasks, including sequencing, verbal and spatial functions, and math tasks,” she said. “Students have trouble with putting together a puzzle, building a bookcase, reading a map, also higher-order thinking and organizing, such as, ‘I have all this homework. How am I going to organize it and get it done?’ We can see a 10 percent reduction in cognitive ability and brain health on many of these measures.”

Tapert thinks that this reduced brain power could be permanent but that more research needs to be done to fully understand what is going on. She and others are looking at whether “the abnormalities we have observed in binge drinkers abate with abstinence.” So far, “we have seen that the white-matter abnormalities are not normalized after just six weeks,” but that might change over time.

In the meantime, DeRiso and others say they expect ERs will continue to treat too many young people for alcohol poisoning, injuries or worse.

“You don’t know how many kids I’ve seen who are never the same,” said Montgomery County police officer William Morrison, who heads the department’s alcohol initiative unit. “They never go back to school, they have brain damage, they stop breathing.”

Students say the culture of binge drinking is not about to change. “The first weekend of freshman year, there is a huge amount of drinking,” said Benjamin Palacios, a senior at Vassar College whose family lives in Chevy Chase. “At Halloween parties last year, 17 kids were sent to the hospital.”

Young people think of drinking as “quite ‘cool,’ “ he said. “And as long as it is, kids will take it as far as they can.”

Hambleton is a freelance writer and editor, and a documentary filmmaker in Chevy Chase.

Click Here for washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/12/06/AR2010120603961.html